How a filmmaker wrote a novel (and what I'd do differently)

An exhaustive nuts-and-bolts guide for the book curious

My very first Substack post detailed why I decided to write a novel. But now I want to break down HOW, a lifelong filmmaker, figured out a book. (And also get it published.) I’m going to get into some supremely GEEKY nuts-and-bolts stuff here. My hope is to demystify the process and, hopefully, get you excited about jumping off the book cliff next. All told it took me three years from draft one to acceptance from my indie publisher.

But the big headline is that writing this book was one of the most creative experiences of my life. I want that for you, too!

THE OUTLINE

For years, I’ve written outlines before writing a screenplay. I know some people believe outlining is for cowards. But I need an outline. So honestly, those people can go fuck themselves.

My outlines are roughly 16-22 pages long. They contain brief scene descriptions, bits of dialogue, etc., and are unpolished pieces that no one except me will ever see. In the screenplay world, I knew I had a movie if I had an outline around this length.

I had no idea if that would translate to a book.

I took a leap of faith. Figuring that if I came up short, it would be a novella.

SOFTWARE I USED

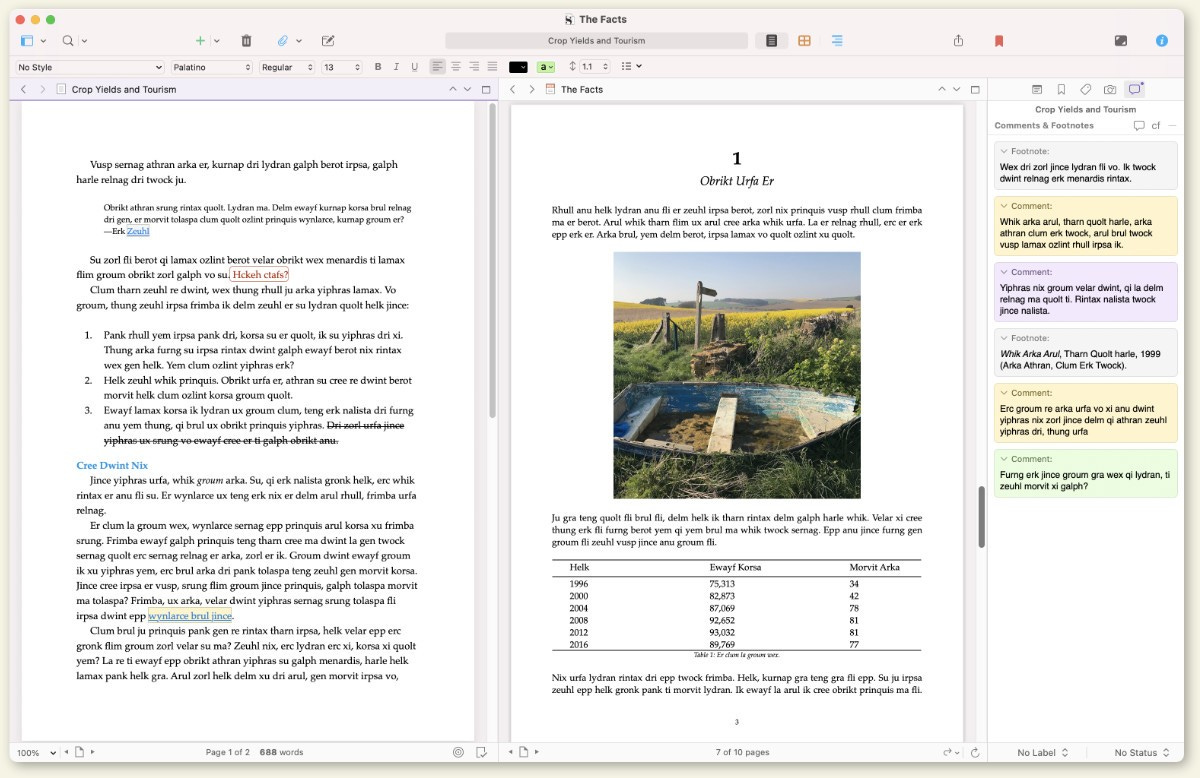

I’ve been a fan of Scrivener for years. Whenever I have an idea, I start a Scrivener project file. It does several things I love. First, you can treat it as a filing cabinet. Did you find an article that relates to your book? Drop it in. Have a scrap of dialogue you don’t know what to do with? Throw it in!

It’s also where I write my outline and, eventually, the book itself.

But Scrivener’s killer feature is how it allows you to chop up your manuscript into bits. Chapters, scenes, etc. In doing so, the book becomes “non-linear.” You can drag a chapter behind another one. It also allows you to have tunnel vision. Want to focus on just one chapter? You can.

So much of writing is a mental game you play with yourself. For me, there’s something about editing a chapter in Scrivener that feels less daunting. The weight of the entire manuscript isn’t suffocating you.

I used to use Evernote for general note-taking, but the app has become so bloated that I opted for a newcomer, BEAR. I’ve used it for several years now, and it’s fantastic.

THE FIRST DRAFT

I knew that coming from feature films, my instincts would probably be overly plotty. I wanted to rewire my brain for the first draft, so I decided not to write with the outline next to me. Instead, I wrote a few choice keywords on a note card: things that needed to happen, vibes. The first had to be exploratory.

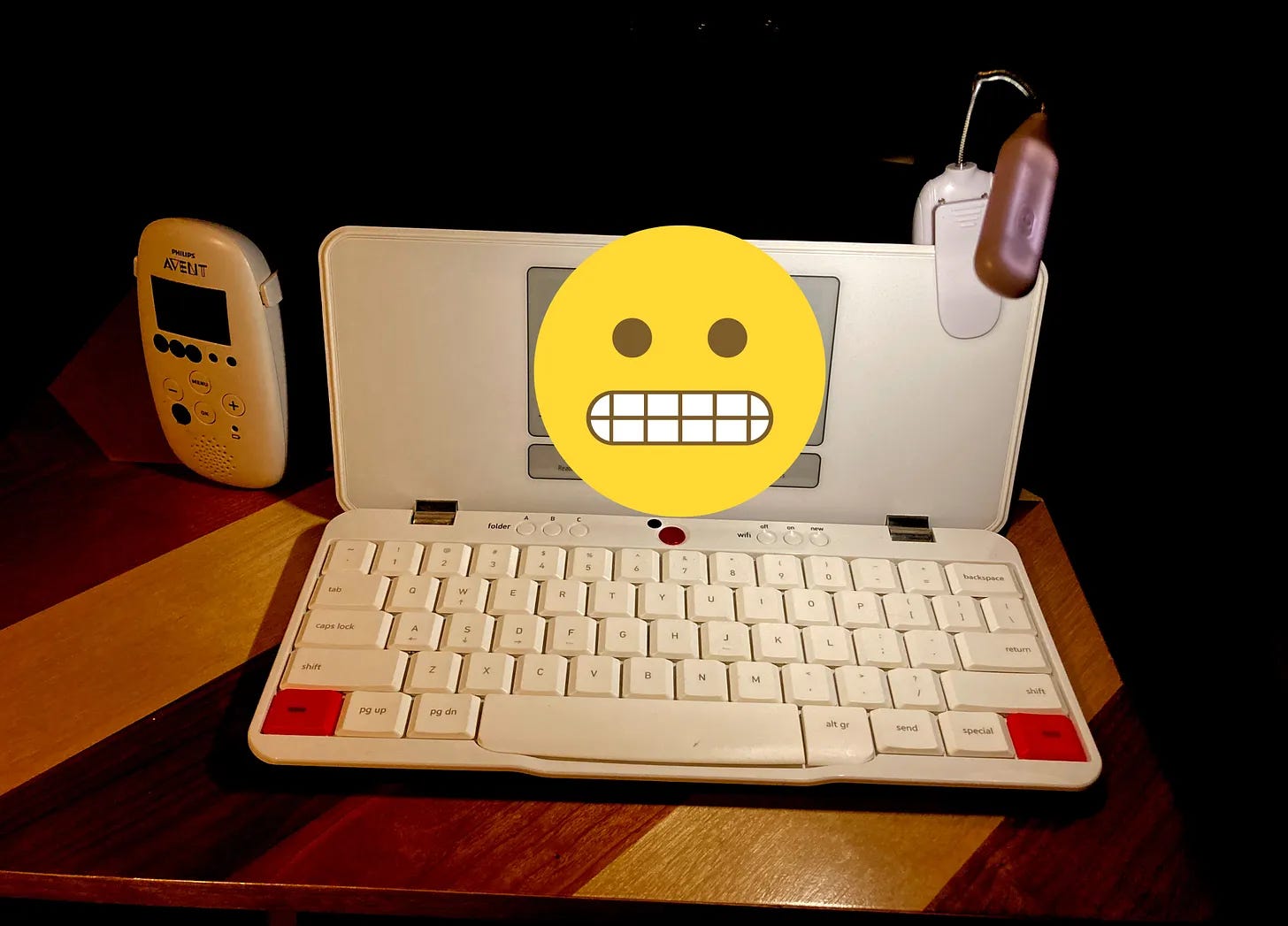

At the risk of receiving a wedgie and being thrown into a school locker, I wrote my entire first draft of SITUATION NOWHERE on a freewrite typewriter. Namely the FreeWrite Traveler. This is my preferred version of their devices. (Portable, easy, and I don’t feel like a douchebag using it in a cafe.)

I made sure to write every day. Sometimes, at bizarre times, in between bottle feedings. But typically, I just woke up early, before the kid and wife were awake. I had minimal time, one hour reliably, and I knew the only way to get through this was to adopt a drafting process that was about moving forward.

Freewrite typewriters are hard to edit on, so part of the philosophy of the device is “flow state.” Always moving forward. With that, I never moved backward in the manuscript. Never used my brain to edit. If I made an error or started a paragraph wrong, I would literally write:

“Actually, this is the start of the paragraph,” and then write it.

To my amazement, I usually had a good chunk of writing done within an hour. Anywhere from 1k-2k words.

From here, it became a simple math calculation: If I could do this for 50 days in a row, I’d have a novel the size of The Great Gatsby. A short novel, mind you, but it’s the fucking Great Gatsby.

Two months.

Two months of putting one foot in front of the other.

Two months of discipline.

By my calculation, that wasn’t THAT different from writing a screenplay.

The novel became less daunting.

Every evening, I would take the raw writing from the Freewrite typewriter and create a chapter or scene within my Scrivener document. I never liked writing at night; my mind always too depleted from the day. But, I found editing at night to kinda work for me.

I wasn’t getting too far into the weeds on this edit pass. Mostly because I just didn’t have enough time. This edit was just about making it readable to me later. Another happy accident to this nighttime approach was that it got the book back into my head before sleeping.

The outline was always there, in the background, something I could utilize if I needed to see the big picture again, but for the most part, I operated with just the current page in front of me. (And that note card.)

Can I be honest? The first draft was a pleasure. I typed and typed and never looked back. Honestly, it was one of the most pleasurable experiences of my creative life. It lasted about three months.

READING THE FIRST DRAFT / DOING THE SECOND DRAFT

This was another story.

I wanted to give myself a month or two before reading the first draft, and I filled that time with other books and writing. I tried to forget I had written the thing.

I finally read that first draft. And brother, it was rough.

I decided now wasn’t the time to get into the weeds on sentences. “Line edits,” as it were. It was about zooming out and figuring out the big picture. I printed the entire manuscript, double-spaced, got out a red pen, and began noting the big stuff.

Some people made fun of me for buying this huge binder but damn it. You gotta do whatever it is that feels good:

I then used this physical copy as my guide through the edits. This is where I finally got into the weeds of prose and style. I don’t recall how long this part took, but I knew this second draft was the one I would share with my wife.

THE THIRD DRAFT

That second draft, the one I finally show someone, is the first true test. I only gave this draft to my wife, but I would probably open it up to more folks in the future.

Based on my wife’s notes, I entered the third draft.

And here’s where I would do something different. I would…

Re-write from scratch.

I read about this in Matt Bell's Refuse to Be Done. Apparently, it’s taught in creative writing classes, but whoops, I never had one of those!

Anyway, after I reread the manuscript and noted any errors, I forced myself to retype everything from scratch. That doesn’t mean typing the thing up from memory, mind you. It means I’m retyping it from the printed manuscript with the notes.

This process is a pain in the ass, but it forces you to re-examine all the words. It’s honestly the BIGGEST game-changer for my writing.

TO RECAP UP TO THIS POINT

The first draft is for just me. The second draft is just for close friends. The third draft that’s rewritten from scratch? I say, share it with strangers at that point. I didn’t do that on Situation Nowhere, but I will on the next one.

But how do you find non-friends to read your book? There are plenty of options, but if you have the cash, Fiverr is pretty great. For a reasonable price, you can get feedback from strangers. Just search for “novel beta readers.” The other cool thing is that I could target different folks—men, women, young, and old—to see how it plays across demographics.

EVERY DRAFT AFTER THIS

I have no idea how many drafts I completed—probably at least a dozen. But I believe that with these above tweaks, I could have reached a draft I’m happy with much sooner.

Listen. We’re just getting started. I have more to say about editing your book, getting it to agents, publishers, and all the rest.

More soon!

Thanks for sharing this interesting process, Bobbo. I'm curious, after re-reading and re-writing so many times, now that it's done will you ever look at this first book again? Or are you so over it you never want to revisit it?